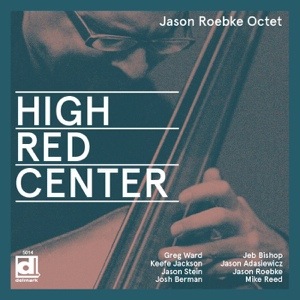

Jason Roebke Octet - High Red Center

Greg Ward – alto saxophone

Keefe Jackson – tenor saxophone

Jason Stein – bass clarinet

Josh Berman – cornet

Jeb Bishop – trombone

Jason Adasiewicz – vibraphone

Jason Roebke – bass

Mike Reed – drums

Chicago is not just the City of the Big Shoulders, as Carl Sandburg immortalized it in his famous poem, but the city of big-toned, solid-to-the-core jazz bassists. There is a legacy of these rock-steady bassists identified with the same “coarse and strong and cunning” intensity as Sandburg’s vision of the Windy City, some born here, others arriving to make their mark – Truck Parham, Milt Hinton, Wilbur Ware, Malachi Favors Maghostut, and of more recent vintage, Kent Kessler, Larry Gray, Harrison Bankhead among them. After 15 years as an important presence on the city’s cutting-edge scene, it may be time for Jason Roebke to be added to the list.

Roebke’s impressive résumé features countless gigs and noteworthy recordings in collaboration with, at one time or another, nearly all of the key players of the current generation, and many of the world’s best improvisers. He is valued for his sound (deep, rich, and natural), which creates a tonal foundation for groups of varying instrumentation; his equilibrium, equal parts stability and alert responsiveness to improvisational conditions; and his versatility. These attributes have held him in good stead with musicians as different in style and temperament as cornetist Rob Mazurek, reedman Tobias Delius, clarinetist Guillermo Gregorio, cellist Fred Lonberg-Holm, and songwriter Van Dyke Parks, to cite just a few.

But it’s not just his bass playing that makes Roebke special. As a composer/conceptualist, he has devised projects as varied and fanciful as solo bass recitals exploring extended techniques; music for dancer Ayako Kato involving bass, keyboards, and ambient field recordings; lyrical pieces for his post-Giuffre jazz trio Rapid Croche; and electronics-infused bop-flavored quartet formats. The manner in which these two perspectives – the mindful bassist and the adventurous composer – combine in High/Red/Center makes this one of his most satisfying achievements to date.

In putting together his first-time Octet, Roebke drew upon past experiences and new ideas. Certainly, the personnel is a cast of the usual suspects – widely recognized, talented musicians who have worked together in diverse configurations for several years, established individual careers, and share a common language of both “inside” and “outside” playing with a dialect that is pure Chicagoese. But Roebke-the-conceptualist wanted to exploit their familiarity and at the same time distort it. As he explains, “I am trying to create a situation where everyone is challenged. The exact instrumentation wasn’t and isn’t at all calculated. The personnel of the group has always been in flux. We usually have nine people but sometimes ten and once seven. I’m not sure that any two gigs have been identical musicians until the performances we did in the run up to the recording.”

To this end, Roebke produced compositions that took advantage of the close-knit qualities of the ensemble even as he took equal pains to confront them with unpredictable options and spontaneous details. Despite his thorough training in composition and arrangements for “standard” big bands and chamber groups, the material for High/Red/Center was designed to be loose and intuitive. Thus, “The writing is about simplicity, in retrospect. My protest of clever composition. Most of the scores are one page only. Some are two pages. A lot of the pieces have purposely non-specific or non-idiomatic parts. Most of the sequences were worked out in rehearsal by the band and are always flexible. I can’t imagine how a piece will come together before I start to rehearse it. I have some basic building blocks to start with but we need to work out an arrangement as a group.”

Remarkably, the music that resulted sounds anything but simple or haphazard. In the time-honored tradition of Charles Mingus, Cecil Taylor, and innumerable early jazz ensembles, uncharted group consensus, focused upon Roebke’s provocative themes and harmonic contexts, led to amazingly tight, complex yet fluid and unified arrangements. These are not just blowing tunes on chord charts, or for that matter, completely free excursions. The compositions have character. Hopefully, a few examples will suffice. Roebke has a knack for writing infectious, propulsive lines, like the bouncy, bright swing – set to ringing vibes and crunchy horns – that opens and closes the title track, the asymmetrical hard-charging head of “No Passengers,” or the implied Dolphyesque angularity that concludes “Double Check” and “Ballin’.” Then, by way of dramatic contrast, he provides the suave, bluesy vamp of “Dirt Cheap,” and a pair of moody ballads: “Shadow” a la Johnny Hodges (via Greg Ward) and “Ten Nights” with a Jeb Bishop trombone soliloquy reminiscent of Bill Harris.

Credit, of course, is due to all of the soloists, consistently imaginative and apt throughout the program, and individually worthy of more attention than I am giving them here. But I think the real story behind High/Red/Center is how the musicians came together, under Jason Roebke’s guidance and conception, to form an ensemble where transparency of voicings, textures, and colors – in other words, what goes on in the background – is as meaningful as the vibrant solos. It’s all part of the same perspective, the manner in which the personalities shape the music. He acknowledges, “It’s a struggle but that’s sort of the point. It’s all about risk and the tension that working at something just beyond our reach creates. When it works, I believe that it leads to an exhilarating listening experience.” I agree.

–Art Lange, Chicago, January 2014